This guide breaks down the OKR meaning, how to write good OKRs, the different types, common mistakes, and real examples across company levels.

What is the definition of OKR?

OKR stands for Objectives and Key Results.

OKR is a goal-setting framework that helps organizations define what they want to achieve and measure whether they're getting there.

It aligns teams around shared priorities and makes visible how everyday work contributes to meaningful business outcomes.

Instead of asking "what are we doing?", OKRs force a different question: "what are we achieving?"

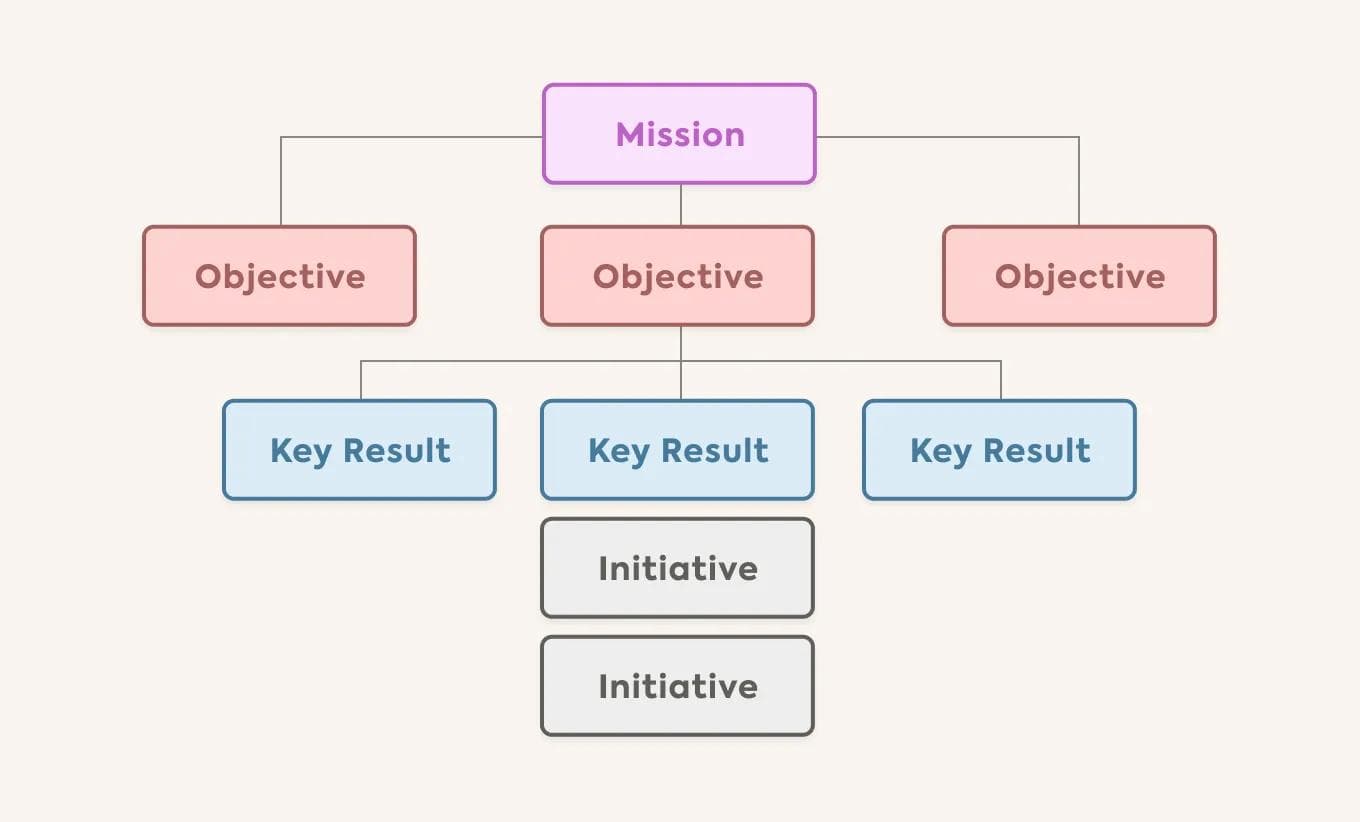

The OKR framework has two core components:

- Objective: a clear, high-level description of what you want to achieve

- Key Results: measurable outcomes that measure whether you got there

An OKR is one Objective paired with 2-4 Key Results. John Doerr, the venture capitalist who brought OKRs from Intel to a young Google and helped popularize the framework worldwide, captured this relationship in a simple formula in his book Measure What Matters:

We will Objective as measured by Key Results.

Let's break down each component.

[Image: okr-structure-diagram.webp - Hierarchy diagram: one Objective at top, three Key Results below it, Initiatives under each KR. Tree/flowchart style in Mooncamp brand colors.]

What are Objectives?

An Objective is the qualitative, inspiring part of an OKR. It defines the what: a clear, high-level description of something your team wants to achieve.

Objectives can span different timeframes, a quarter, a half-year, or even longer, though most teams default to quarterly cycles.

Good Objectives are moonshots: they should feel uncomfortable, stretching your team to the edge of what's possible without tipping into fantasy.

The point is to force prioritization. When you only have room for 2-4 Objectives, you can't hide behind a long list of "nice to haves." Every Objective should connect directly to your company's strategy, mission, or vision.

- Qualitative, not quantitative: no numbers in the Objective itself

- Ambitious enough that achieving 70% still represents real progress

- Few in number (2-4 per team) to maintain ruthless focus

- Tied to a clear timeframe and owned by a specific team

- "Become the undisputed market leader in our category"

- "Deliver a product experience that customers can't stop talking about"

- "Build a world-class team that attracts top talent from competitors"

[Image: objective-hierarchy.webp - Hierarchy diagram. Company Objective at top: "Become the most trusted brand in our industry." Nested below: Marketing Objective "Build a content engine that establishes us as the go-to thought leader" and Sales Objective "Create a customer experience that drives word-of-mouth referrals." Indented tree structure with connecting lines, Mooncamp brand colors.]

What are Key Results?

Key Results are the quantitative metrics that ground your Objective in reality. They break an ambitious aspiration into tangible milestones, so there's never a debate about whether you succeeded or not.

Every Key Result must have a number. Without one, you're back to vague intentions.

Key Results also serve as an accountability mechanism: when an Objective spans several months, it's easy to lose track. Measurable Key Results keep progress visible and make it obvious when things go off course.

- Always include a number: if it can't be measured, it's not a Key Result

- Measure outcomes (what changed), not activities (what you did)

- Include a start value and a target value so progress is unambiguous

- Limit to 2-4 per Objective to maintain focus

- "Increase Net Promoter Score from 32 to 55"

- "Grow monthly recurring revenue from $500K to $1.2M"

- "Reduce customer churn from 8% to 3%"

[Image: key-result-hierarchy.webp - Hierarchy diagram. Marketing Objective at top: "Build a content engine that establishes us as the go-to thought leader." Nested below: Marketing Key Result "Increase organic traffic from 50K to 150K monthly visits" and Marketing Key Result "Grow email subscribers from 5,000 to 20,000." Zoomed-in view with the company objective and sales objective visible but faded in the background. Mooncamp brand colors.]

An Initiative is a focused effort geared toward achieving one or more Key Results. Initiatives describe the actual work: the projects, experiments, and tasks your team executes. Because they're separate from Key Results, you can swap an initiative that isn't working without changing the goal itself.

Objective | Key Result | Initiative | |

|---|---|---|---|

Focus | Direction | Measurement | Action |

Type | Qualitative | Quantitative | Activity-based |

Answers | "Where do we want to go?" | "How do we know we got there?" | "What will we do?" |

Example | Become the most trusted brand in our industry | Increase NPS from 32 to 55 | Launch a customer feedback program |

Here's a complete OKR example:

A brief history of the OKR method

OKRs were invented by Andy Grove at Intel in the 1970s, building on Peter Drucker's Management by Objectives from 1954.

In 1954, Peter Drucker introduced Management by Objectives (MBO) in The Practice of Management: instead of managers dictating tasks, they agreed on goals with employees. But MBO had weaknesses: goals were annual, progress was hard to measure, and the process was top-down and bureaucratic.

In the 1970s, Andy Grove at Intel kept Drucker's idea and added Key Results: measurable outcomes that tracked real progress, not just completed tasks. He also shortened the cycle from annual to quarterly, forcing more frequent reassessment.

In 1999, John Doerr, a former Intel employee, introduced OKRs to a young Google with just 40 employees. Larry Page and Sergey Brin adopted the framework company-wide, and Doerr later popularized it globally through his book Measure What Matters.

Today, OKRs are used by companies like Spotify, LinkedIn, Samsung, and The Gates Foundation, from 10-person startups to 100,000-person enterprises.

[Image: okr-history-timeline.webp - Horizontal timeline: Drucker's MBO in 1954, Andy Grove at Intel in the 1970s, John Doerr brings OKRs to Google in 1999, widespread adoption from 2010s onward.]

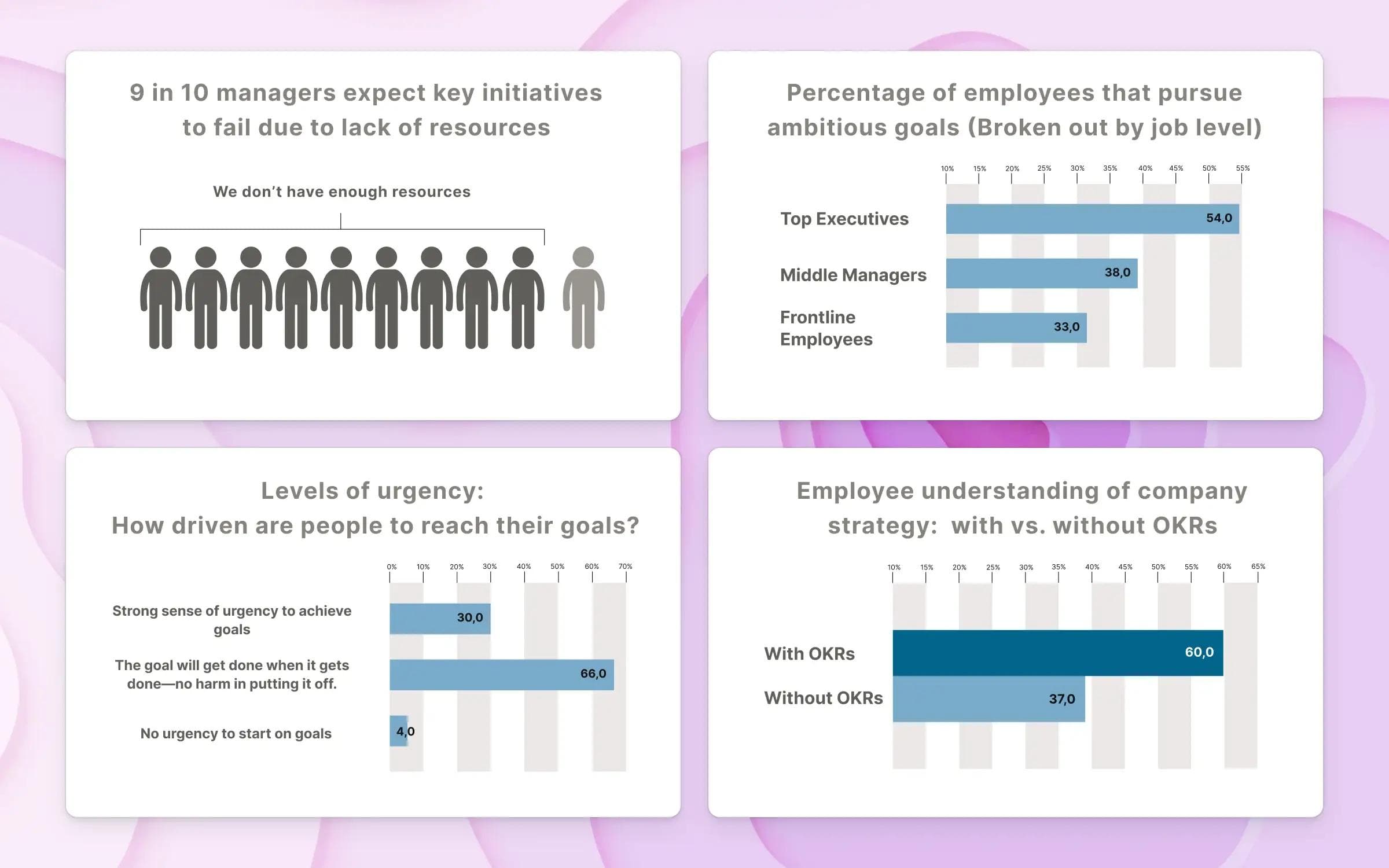

Why use OKRs?

83% of organizations using OKRs report a positive impact on their business, according to Mooncamp's OKR Impact Report 2022. That number rises when goals are transparent, reviewed regularly, and connected to company strategy.

OKR benefits

OKRs deliver results through five core mechanisms, often referred to as FACTS:

- Focus: Limiting OKRs to 2-4 per team forces prioritization. When everything is a priority, nothing is.

- Alignment: Team OKRs ladder up to company OKRs, so every department pulls in the same direction instead of optimizing in silos.

- Commitment: When teams help set their own OKRs, they own the outcome. OKRs create commitment that top-down mandates rarely achieve.

- Tracking: Measurable Key Results make progress undeniable. Weekly check-ins and a clear score at the end of each cycle mean nothing gets ignored.

- Stretching: OKRs push teams beyond business-as-usual. Ambitious goals that feel 70% achievable drive more progress than safe, conservative targets.

Beyond FACTS, OKRs also improve collaboration (shared OKRs break down silos between departments) and engagement: research from Harvard Business Review shows that aligned employees are more than twice as likely to be top performers.

A full breakdown of each benefit: Benefits of OKRs

What are the types of OKRs?

Not all OKRs work the same way. Different types serve different purposes, and knowing the distinction helps teams set goals that fit the situation.

Committed vs aspirational OKRs

The most important distinction in the OKR method is between committed and aspirational OKRs, a framework Google uses internally.

Committed OKRs are must-dos: targets the team commits to hitting 100%, like a product launch, a compliance deadline, or a contractual obligation. Missing a committed OKR is a serious problem.

Aspirational OKRs (also called stretch goals) are ambitious by design: 70% completion counts as success. If you hit 100% of your aspirational OKRs every quarter, your targets aren't ambitious enough.

Most teams use a mix: committed OKRs for business-critical goals, aspirational OKRs for growth bets.

Company, team, and individual OKRs

OKRs also differ by level.

Company OKRs set the strategic direction for the entire organization. They are typically owned by the leadership team and define the 2-4 most important priorities for the quarter.

Team OKRs translate company priorities into department-level goals. Each team's OKRs should support at least one company OKR, creating alignment across the organization.

Individual OKRs connect a person's daily work to team goals. They are less common in OKR programs than company and team OKRs: many organizations skip individual OKRs entirely, especially when starting out.

Annual vs quarterly OKRs

Most teams operate on a quarterly cadence: 90 days is long enough to achieve something meaningful and short enough to stay focused. Some organizations also set annual OKRs at the company level to anchor long-horizon ambitions, using quarterly OKRs as stepping stones toward them.

OKR vs KPI

OKRs drive change. KPIs monitor health.

A KPI (Key Performance Indicator) is a metric that tracks ongoing business performance, such as revenue, churn rate, or customer satisfaction. An OKR is a goal that drives improvement toward a defined outcome.

[Image: okr-vs-kpi-visual.webp - Two icons: a changing road sign (OKR, representing direction and change) vs a speedometer (KPI, representing ongoing health monitoring).]

OKR | KPI | |

|---|---|---|

Purpose | Drive change and improvement | Monitor ongoing performance |

Direction | Future-oriented | Status quo / past |

Timeframe | Quarterly (typically) | Ongoing |

Ambition | Stretch goals (70% = success) | Targets (100% = expected) |

Scope | 3-5 per team | Many per department |

Example | "Increase NPS from 30 to 50" | "Current NPS: 30" |

KPIs flag problems; OKRs fix them. When your churn rate KPI rises from 5% to 8%, that's a signal to create an OKR: "Reduce customer churn, as measured by bringing churn rate from 8% to 4%."

Most organizations use both: KPIs as the ongoing dashboard, OKRs as the quarterly compass.

A full comparison: OKR vs KPI

How to write great OKRs

A great OKR has an inspiring Objective and 2-4 measurable Key Results.

The Objective provides direction. The Key Results provide evidence of success.

OKR formula: We will [Objective] as measured by [Key Result 1], [Key Result 2], and [Key Result 3].

This formula forces you to separate the aspiration (Objective) from the evidence (Key Results).

Writing Objectives

An Objective should make your team say "Yes, that's worth working toward."

Objectives typically fall into one of three types: build something new (a product, capability, or market position), improve something existing (speed, quality, conversion rate), or innovate by rethinking an approach entirely.

Knowing the type helps keep the Objective focused.

A "build" Objective might read: "Launch our first enterprise product." An "improve" Objective might read: "Deliver a faster, more reliable checkout experience."

Rules for writing Objectives:

- Keep it qualitative: No numbers. The Objective is the inspiration; Key Results handle the metrics.

- Make it inspiring: "Dominate our category" beats "Grow market share."

- Be ambitious: OKRs should push the team beyond business-as-usual. Aim for what feels 70% achievable.

- Time-bound it: Tie it to a cycle. Most teams use quarterly OKRs.

- Give it an owner: Every Objective needs a team (or person) who is responsible for it.

Bad Objective: "Improve marketing"

Too vague. Improve how? Why? No one would rally behind this.

Good Objective: "Become the go-to thought leader in our industry"

Inspiring, directional, and ambitious. The team knows what success looks like.

Writing Key Results

Key Results are the evidence that the Objective has been achieved.

The most common mistake is writing tasks (outputs) instead of outcomes.

Rules for writing Key Results:

- Make it measurable: Every Key Result needs a number. "Improve satisfaction" is not a Key Result. "Increase CSAT from 72 to 90" is.

- Focus on outcomes, not output: Measure what changed, not what you did. "Write 10 blog posts" is a task. "Increase organic traffic from 5K to 15K monthly visitors" is an outcome.

- Be specific: Include a starting value and a target value so progress is unambiguous.

- Limit to 2-4 per Objective: More than four Key Results dilutes focus.

Bad Key Result: "Write 10 blog posts"

This is a task (output), not an outcome. You could write 10 posts and still see zero traffic growth.

Good Key Result: "Increase organic traffic from 5,000 to 15,000 monthly visitors"

Measurable, outcome-focused, and directly tied to business impact.

Setting Initiatives

Initiatives are the actions that drive Key Results forward.

- Key Result: "Increase organic traffic from 5K to 15K monthly visitors"

- Initiative 1: Publish 2 SEO-optimized articles per week

- Initiative 2: Rebuild the top 10 landing pages for search intent

If an Initiative isn't working, you can swap it for a different one without changing the Key Result.

[Image: okr-writing-checklist.webp - Checklist card showing two columns: what Objectives should be (qualitative, inspiring, ambitious, time-bound, team-owned) and what Key Results should be (measurable, outcome-focused, specific, limited to 2-4 per Objective).]

Here's a full, well-crafted OKR:

Objective | Become the go-to thought leader in our industry |

Key Results |

|

Step-by-step guidance: How to Write OKRs

Good vs bad OKRs

A good OKR has an inspiring Objective and measurable, outcome-focused Key Results.

[Image: good-vs-bad-okr.webp - Two OKR cards side by side: one in red showing a bad OKR with a vague Objective and output-focused Key Results, one in green showing a good OKR with a specific Objective and outcome-focused Key Results.]

Bad OKR | Good OKR | |

|---|---|---|

Objective | "Improve our product" | "Deliver a product experience that users love" |

Key Result 1 | "Ship 10 new features" | "Increase daily active users from 1,200 to 3,000" |

Key Result 2 | "Fix bugs" | "Reduce average bug resolution time from 5 days to 1 day" |

Key Result 3 | "Make users happier" | "Increase in-app NPS from 25 to 50" |

Problem | Vague Objective, output-focused KRs, nothing measurable | Inspiring Objective, outcome-focused KRs, clear metrics |

The bad OKR sounds reasonable, but "Improve our product" could mean anything, "Ship 10 features" rewards output over impact, and "Make users happier" cannot be verified.

The good OKR gives the team an exact definition of success at the end of the quarter: specific numbers to hit, and an Objective worth working toward.

Three patterns that make OKRs bad:

- Too vague: "Improve marketing" gives no direction. Without specificity, teams interpret the Objective differently and pull in different directions.

- Output-focused: "Write 10 blog posts" tracks activity, not impact. Measure the outcome (traffic, leads, engagement) instead.

- Not measurable: "Make customers happier" cannot be verified. Replace it with a number: "Increase CSAT from 72 to 90."

Common OKR mistakes

The most common OKR mistake is setting too many goals, which destroys the focus that makes OKRs valuable.

- Setting too many OKRs: More than 3-4 OKRs per team means nothing gets real focus. Fewer goals lead to better results.

- Confusing Key Results with tasks: "Launch redesigned homepage" is a task. "Increase homepage conversion rate from 2% to 5%" is a Key Result. Key Results track what changed, not what you did.

- No connection to strategy: OKRs that float in isolation don't move the company forward. Every team OKR should trace back to a company-level goal.

- Setting OKRs top-down only: When leadership dictates every OKR, teams lose ownership. The best approach combines top-down direction (leadership sets company OKRs) with bottom-up input (teams propose their own OKRs to support them).

- Not reviewing OKRs regularly: Setting OKRs and forgetting them until the end of the quarter defeats the purpose. Weekly or biweekly check-ins keep progress visible and allow course corrections.

- Tying OKRs to compensation: When bonuses depend on OKR scores, teams set easy targets to protect their pay. Keep OKRs ambitious by separating them from compensation.

The full list with fixes: OKR Mistakes to Avoid

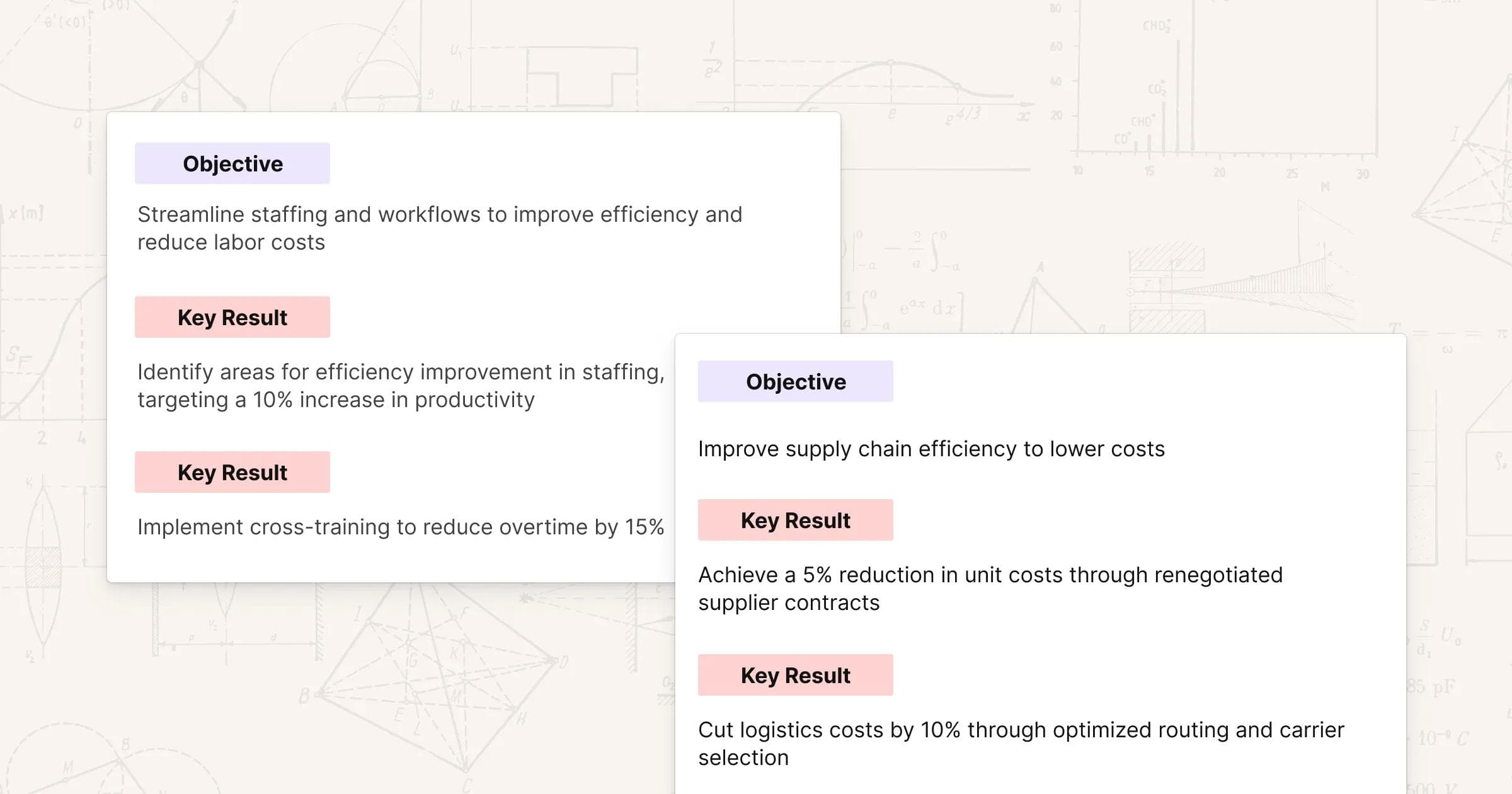

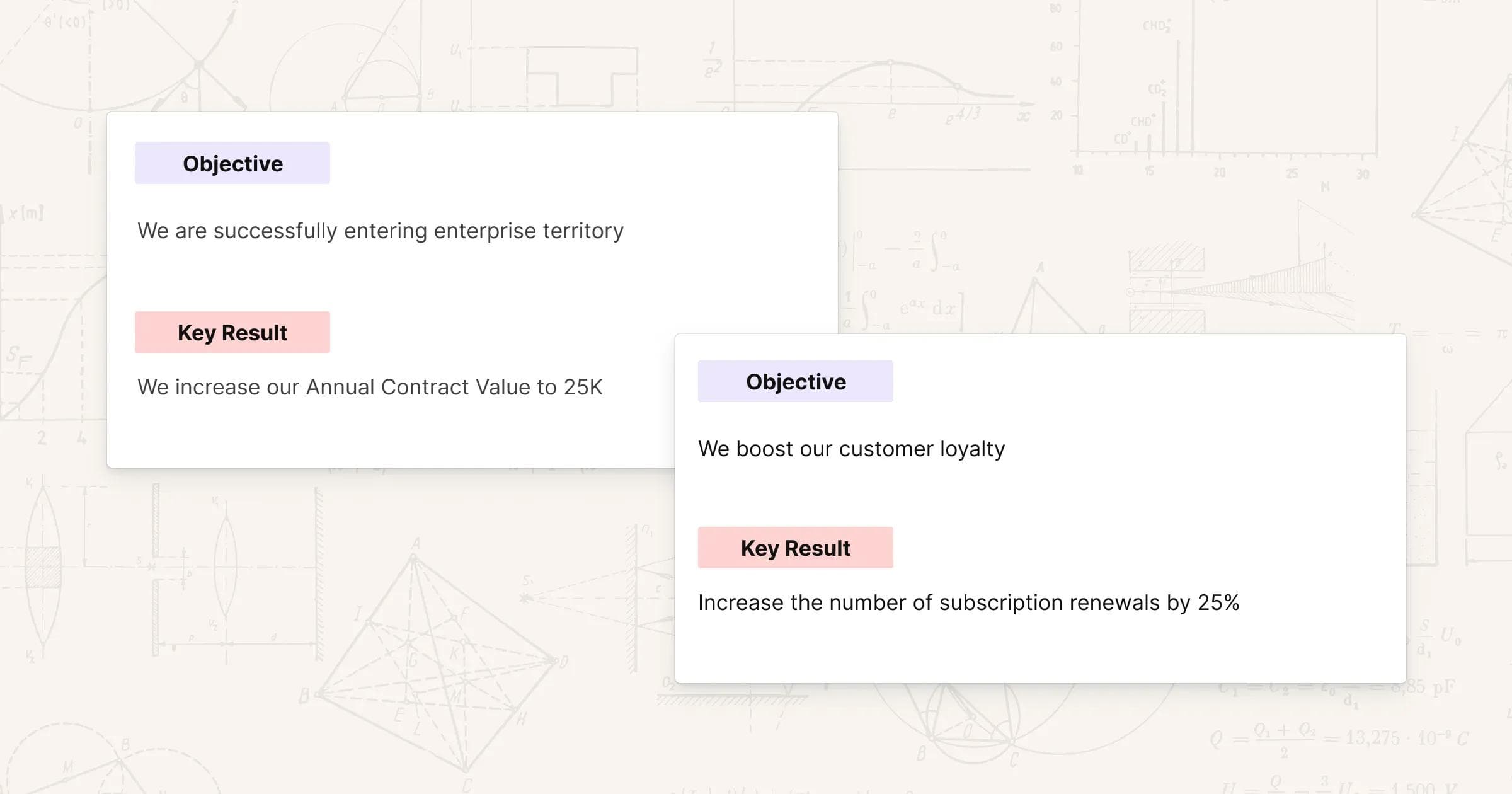

OKR examples

The best way to understand OKRs is to see them in action.

OKRs work at multiple levels: company, team, and individual.

Company OKRs set the strategic direction; team OKRs translate that direction into department-level priorities; individual OKRs connect daily work to team goals. This cascade ensures every OKR in the organization traces back to a company priority.

Level | Owner | Example Objective |

|---|---|---|

Company | Leadership team | Achieve product-market fit and set the foundation for scale |

Team | Marketing team | Build a content engine that drives predictable inbound growth |

Individual | Content lead | Establish SEO as a repeatable growth channel |

Company-level OKR:

A company-level OKR sets the strategic direction for the entire organization. All team OKRs should align with it.

Objective | Achieve product-market fit and set the foundation for scale |

Key Results |

|

Marketing team OKR:

This OKR focuses on outcomes (traffic, leads, conversions), not activities. Each Key Result includes a starting value and a target value.

Objective | Build a content engine that drives predictable inbound growth |

Key Results |

|

Product team OKR:

This OKR focuses on the user experience, not on shipping features. The Key Results measure whether users succeed with the product.

Objective | Deliver an onboarding experience that turns signups into power users |

Key Results |

|

For more examples across departments and industries: OKR Examples Library

Frequently asked questions

What does OKR stand for?

OKR stands for <strong>Objectives and Key Results</strong>. It is a goal-setting framework that pairs qualitative goals (Objectives) with measurable outcomes (Key Results) to create focus and accountability.

What are the three components of OKRs?

The three components are <strong>Objectives</strong> (qualitative goals), <strong>Key Results</strong> (measurable outcomes), and <strong>Initiatives</strong> (the actions and projects that drive progress). Objectives and Key Results are the core; Initiatives are a common addition.

What's the difference between OKRs and KPIs?

<strong>KPIs are the dashboard</strong>: fuel gauge, engine temperature, speed, the things you monitor to keep running smoothly. <strong>OKRs are the roadmap</strong>: they tell you where you're going and how you'll know you've arrived. KPIs flag problems; OKRs fix them. Learn more: <a href="/blog/okr-vs-kpi">OKR vs KPI</a>

How many OKRs should a team have?

Most teams should have <strong>2-4 Objectives per quarter</strong>, each with 2-4 Key Results. More than that dilutes focus. If everything is a priority, nothing is.

How often should OKRs be reviewed?

OKRs should be reviewed at least <strong>every two weeks</strong>, ideally weekly. Regular <a href="/blog/okr-check-in">check-ins</a> keep progress visible and allow teams to adjust before it's too late. A formal <a href="/blog/okr-review">OKR review</a> happens at the end of each cycle.

What percentage makes an OKR successful?

For aspirational OKRs, <strong>70% completion is considered a success</strong>. Hitting 100% every quarter suggests the goals weren't ambitious enough. For committed OKRs (must-dos), 100% is the expectation. Learn more: <a href="/blog/okr-scoring">OKR Scoring</a>

Should bonuses be tied to OKRs?

<strong>No.</strong> Tying compensation to OKR scores encourages sandbagging: teams set easy targets to protect their pay. OKRs work best when separated from bonuses and used purely for learning, alignment, and ambitious goal-setting.

What's the difference between OKRs and MBO?

<strong>MBO (Management by Objectives)</strong> is OKR's predecessor, introduced by Peter Drucker in 1954. OKRs improve on MBO by adding measurable Key Results, shortening cycles from annual to quarterly, and making goals transparent across the organization rather than private between manager and employee.

What's the difference between OKRs and SMART goals?

SMART is a format for writing individual goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound). OKRs are a <strong>framework</strong> that includes goal-setting, alignment, transparency, and regular check-ins. One key difference: SMART emphasizes "Achievable," which can discourage ambitious thinking. OKRs deliberately encourage stretch goals where 70% completion counts as success.

Is Google still using OKRs?

<strong>Yes.</strong> Google has used OKRs since 1999, when John Doerr introduced the framework to the company's 40 employees. Google still uses OKRs across the organization to set quarterly goals and drive alignment.

Can you use OKRs and KPIs together?

<strong>Absolutely.</strong> KPIs monitor ongoing business health (like churn rate or revenue). When a KPI signals a problem, you create an OKR to fix it. Key Results can even reference KPI metrics directly.

Who should own OKRs?

Every OKR needs a clear owner, usually a <strong>team</strong>, not an individual. Company-level OKRs are owned by the leadership team. Shared OKRs across teams need a single designated owner to avoid diffusion of responsibility.

How do I write OKRs for something that seems unmeasurable?

Almost anything can be measured with the right proxy. Ask: <strong>"How will I know when this Objective has been achieved?"</strong> "Improve team culture" sounds unmeasurable, but you could track employee satisfaction scores, voluntary turnover rate, or internal referral rates. Focus on outcomes (what changed), not outputs (what you did).

How long does it take to implement OKRs?

Most organizations need <strong>1-2 quarters</strong> to find an approach that works. The first cycle is a learning experience: expect awkward OKRs, imperfect check-ins, and many questions. By the second or third cycle, teams find their rhythm. A clear <a href="/blog/okr-implementation">implementation plan</a> and a dedicated OKR champion speeds things up.

Who should be in charge of the OKR program?

Appoint an <strong>OKR champion</strong> (sometimes called an OKR ambassador or <a href="/blog/okr-master">OKR master</a>): a single point of contact responsible for program management, training, and quality assurance. In smaller organizations, this is often a founder or head of operations; in larger ones, it's a dedicated role.

What are some common mistakes to avoid with OKRs?

The most common mistakes are: <strong>setting too many OKRs</strong> (losing focus), <strong>confusing Key Results with tasks</strong> (measuring output instead of outcomes), <strong>not connecting OKRs to strategy</strong> (goals floating in isolation), and <strong>not reviewing OKRs regularly</strong>. Tying OKRs to bonuses is another frequent pitfall. See the full list: <a href="/blog/okr-mistakes">Common OKR Mistakes</a>